A more detailed history of the area can be seen on the Trust’s company website.

Seven Dials is the only quarter of London remaining largely intact from late Stuart England – the late 17th century. It was the creation of two of the century’s most extraordinary figures, Thomas Neale MP (1641-1699) and Edward Pierce (1630-1695). Neale, known as ‘The Great Projector’, was an MP for thirty years, a member of 62 Parliamentary committees, Master of the Mint and of the Transfer Office and Groom Porter to Charles II, James II and William III. His plethora of projects ranged from Seven Dials and Tunbridge Wells to mining in Maryland and Virginia and he introduced ‘lotteries after the Venetian manner’, the precursor of our National Lottery. Neale’s influence derived by his combining the three key worlds of late Stuart England: the County, the Court and the City. Edward Pierce was the leading stonemason of his generation, the greatest sculptor of the 17th century, a renowned architect and artist and Master of the Painter Stainers Company in 1693.

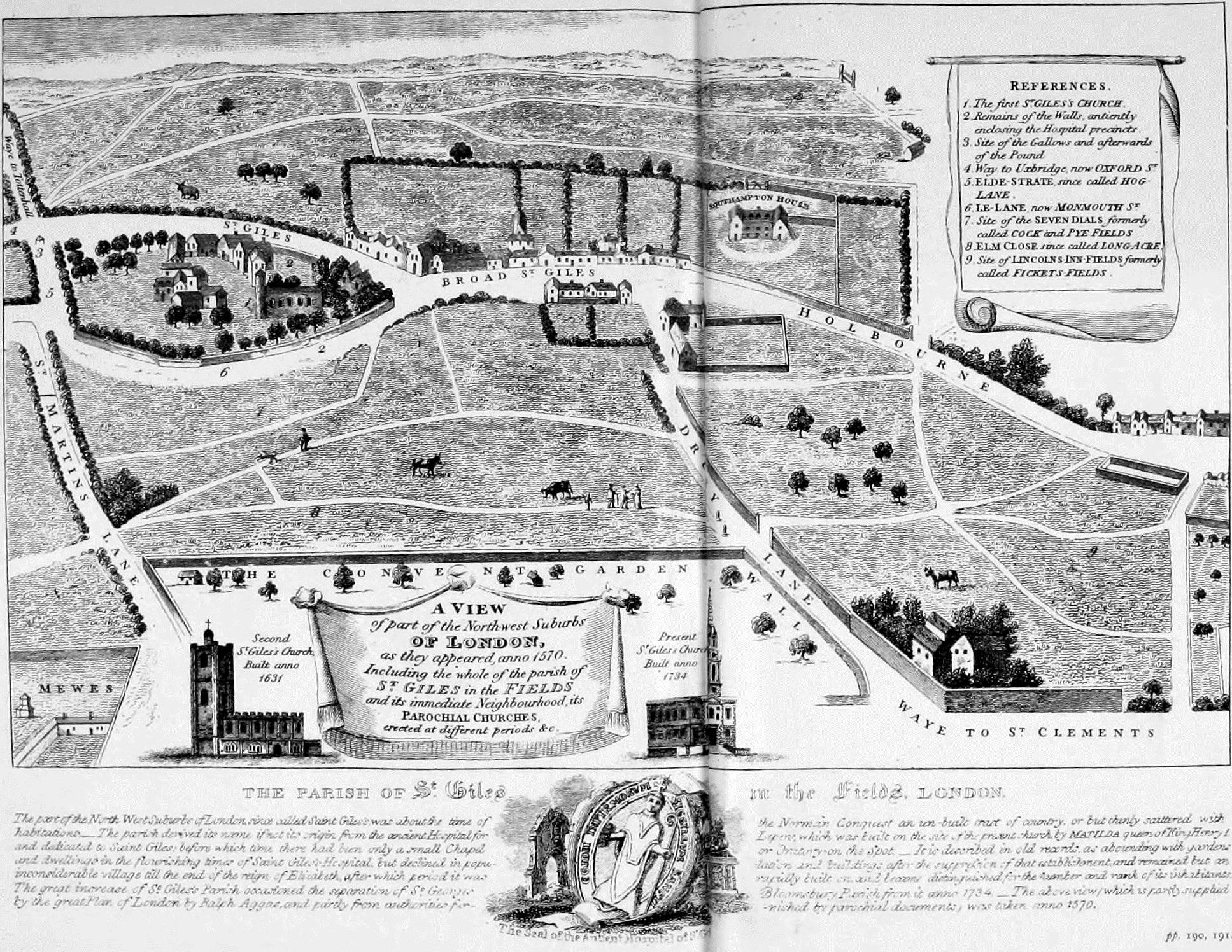

In the Middle Ages, the land on which Seven Dials is situated belonged to the Hospital of St. Giles, a leper hospital which was taken over by Henry VIII in 1537. The Crown subsequently let the hospital land on a series of leases. In 1690 Thomas Neale obtained a lease of Marshland Close ‘intending to improve the saide premisses by building’. He converted his Crown leasehold into a freehold in 1692.

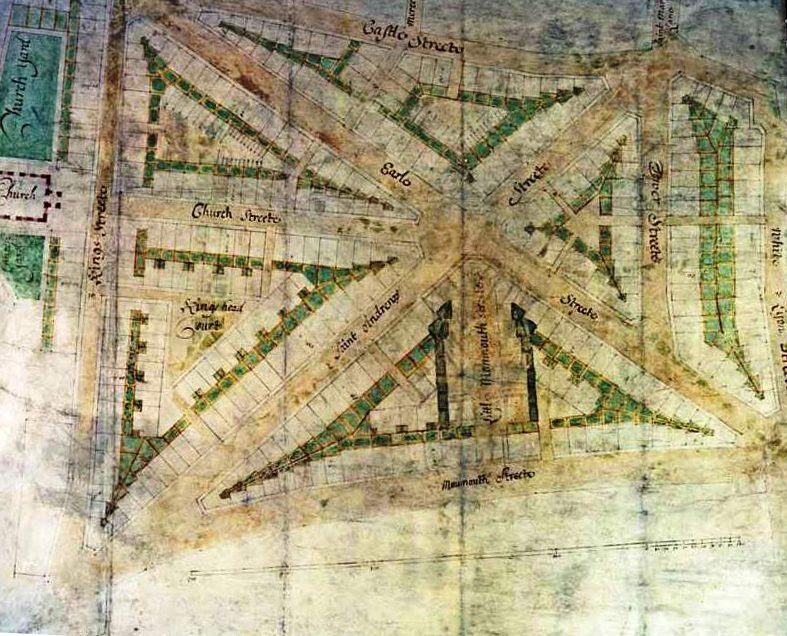

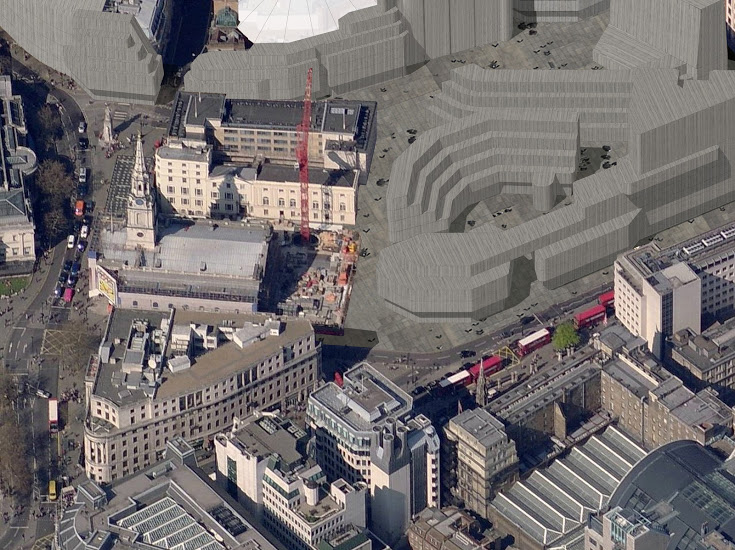

His ‘planning application’ to Sir Christopher Wren, Surveyor General, showed six streets and a church. In fact, the church was never built and Neale laid out seven streets. By adopting a star-shaped plan with radiating streets, he significantly increased the total site frontages and number of plots to be let for building, greatly enhancing the overall site value as rents were charged by frontage.

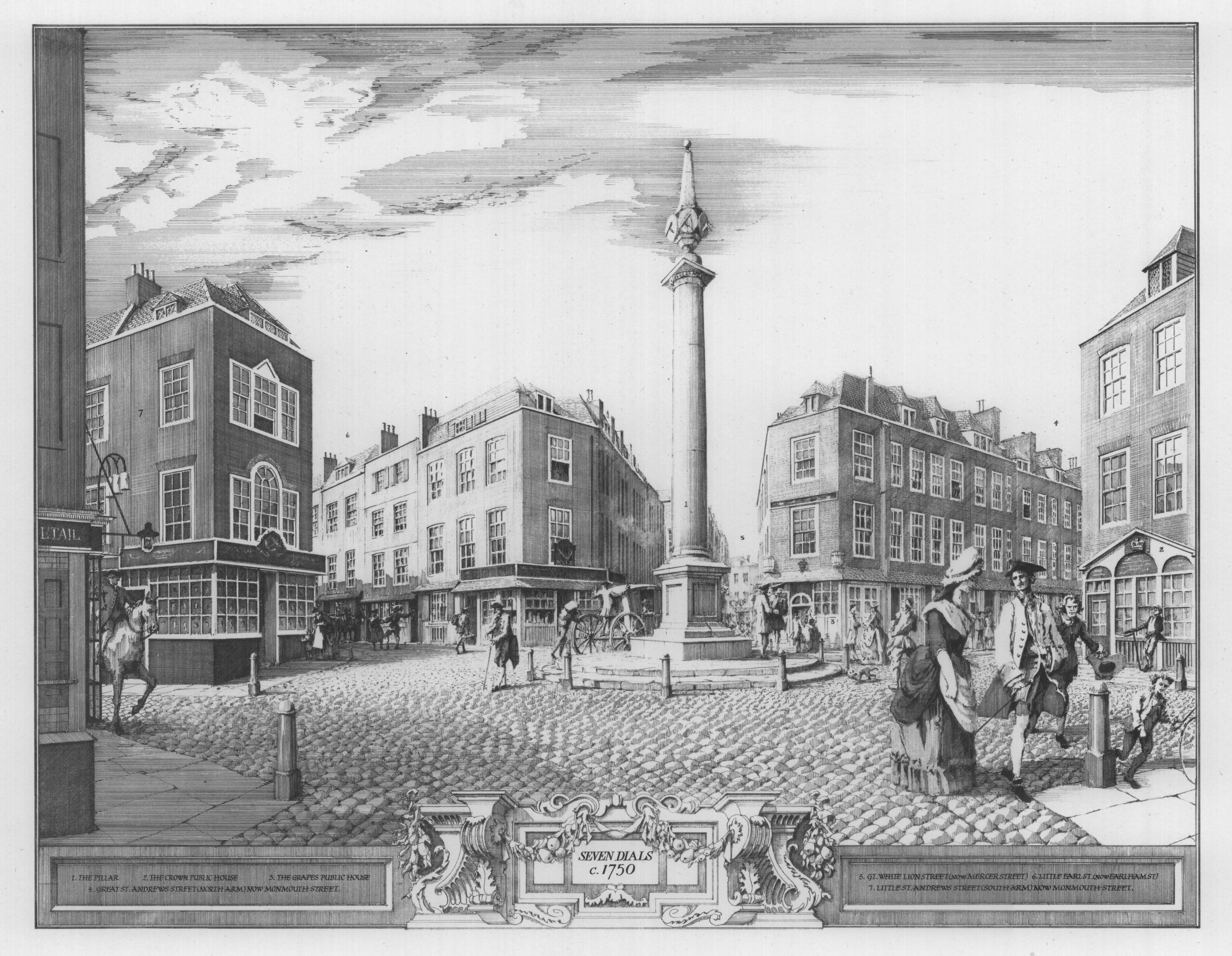

Construction began in March 1693 and most of the surviving building leases are dated 1694. In October of that year the diarist John Evelyn recorded a visit to the site and his inspection of Edward Pierce’s Doric column at the centre.

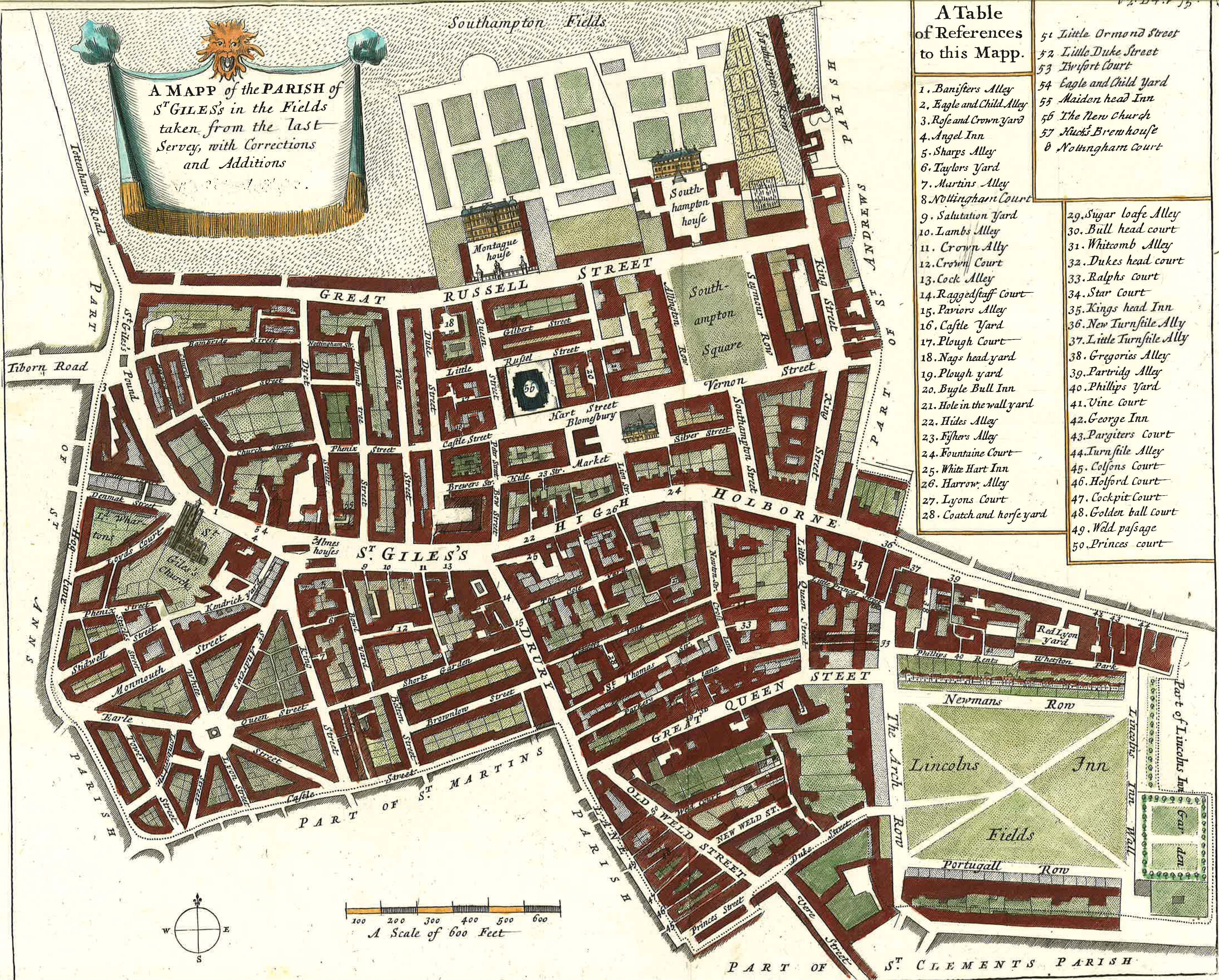

As can be seen from Strype’s map of 1725, the layout was quite different from the then fashionable residential squares and is unique in London town planning. Professor Baer’s fascinating research paper demonstrates that from the outset this was a mixed-use development, not just residential. There were covenants written into each lease to avoid noisy and smelly activities, an early and interesting attempt at estate management. From the outset, Neale envisaged what we would now call a high-density, mixed-use area with residential, suitable businesses and leisure. This was almost certainly unique at the time though, ultimately, not successful.

The first inhabitants of Seven Dials were respectable gentlemen, lawyers and prosperous tradesmen. The social cachet of the area was short-lived however. As fashion marched steadily westwards, the star-shaped layout came to be seen as confused and cramped rather than novel. In the 1730s the then owner, James Joye, broke up the freehold, selling off the triangular sections separately. In the absence of a single freeholder, there was no one to enforce Neale’s careful restrictive covenants. The area became increasingly commercialised, with houses converted into shops, lodgings and factories.

Though not as notorious as the neighbouring St. Giles ‘rookery’ to the north, Seven Dials had something of a reputation for rough behaviour. Numerous incidents of mob violence are recorded in the parish minutes. The reason given for the removal of the Sundial Pillar by the Paving Commissioners in 1773 was that it acted as a magnet attracting undesirables.

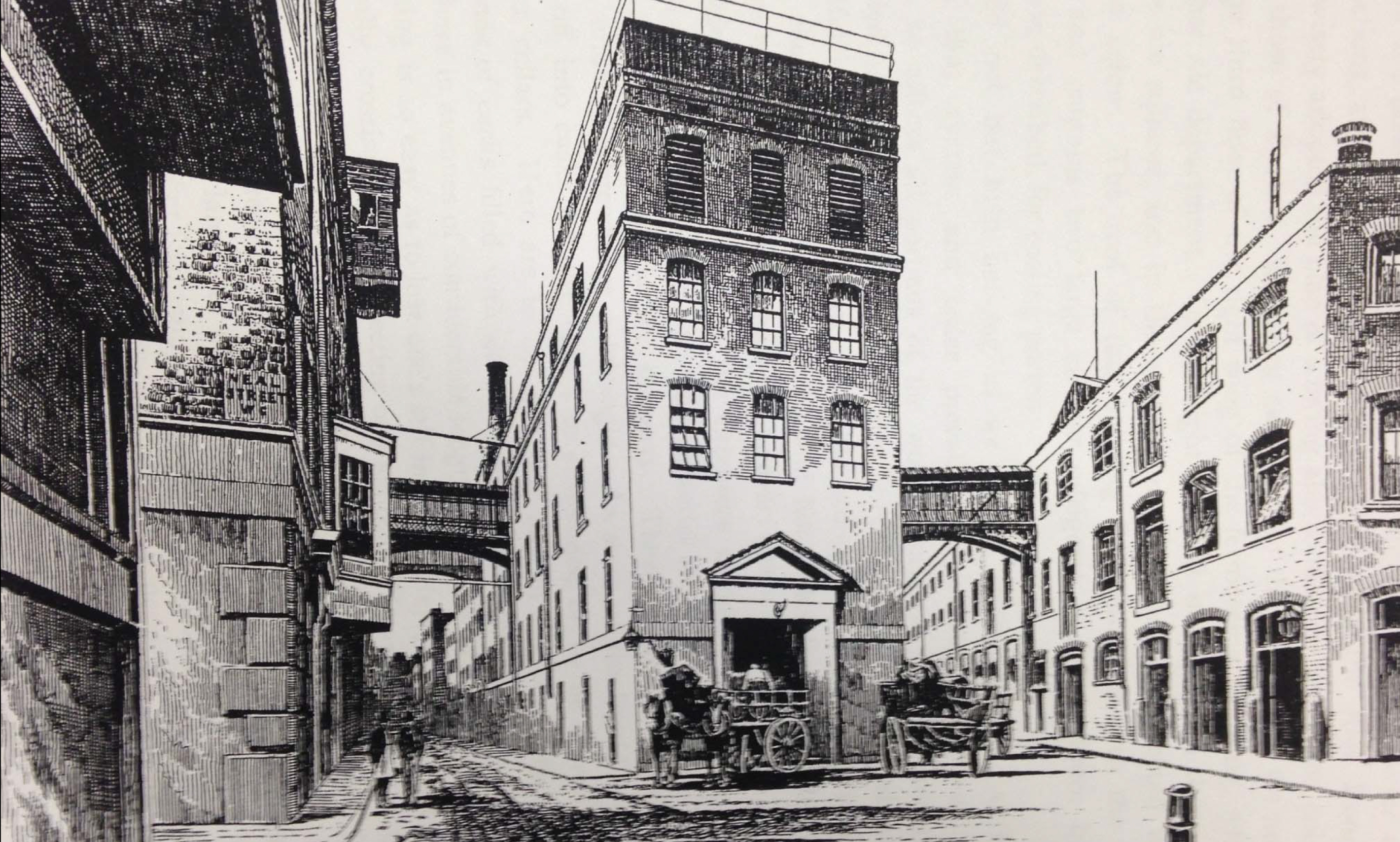

Combe’s Woodyard Brewery was started in 1740 and, in the next hundred years, spread over most of the southern part of Seven Dials. Comyn Ching, the architectural ironmongers, were in business in Shelton Street from the early 1700s, their lease signed by William & Mary. Elsewhere there were woodcarvers, straw hat manufacturers, pork butchers, watch repairers, wig makers and booksellers, as well as several public houses.

In the 1790s there was considerable reconstruction as leases were renewed. The facades of many of the older houses are now of that date, as are several of the painted timber shopfronts.

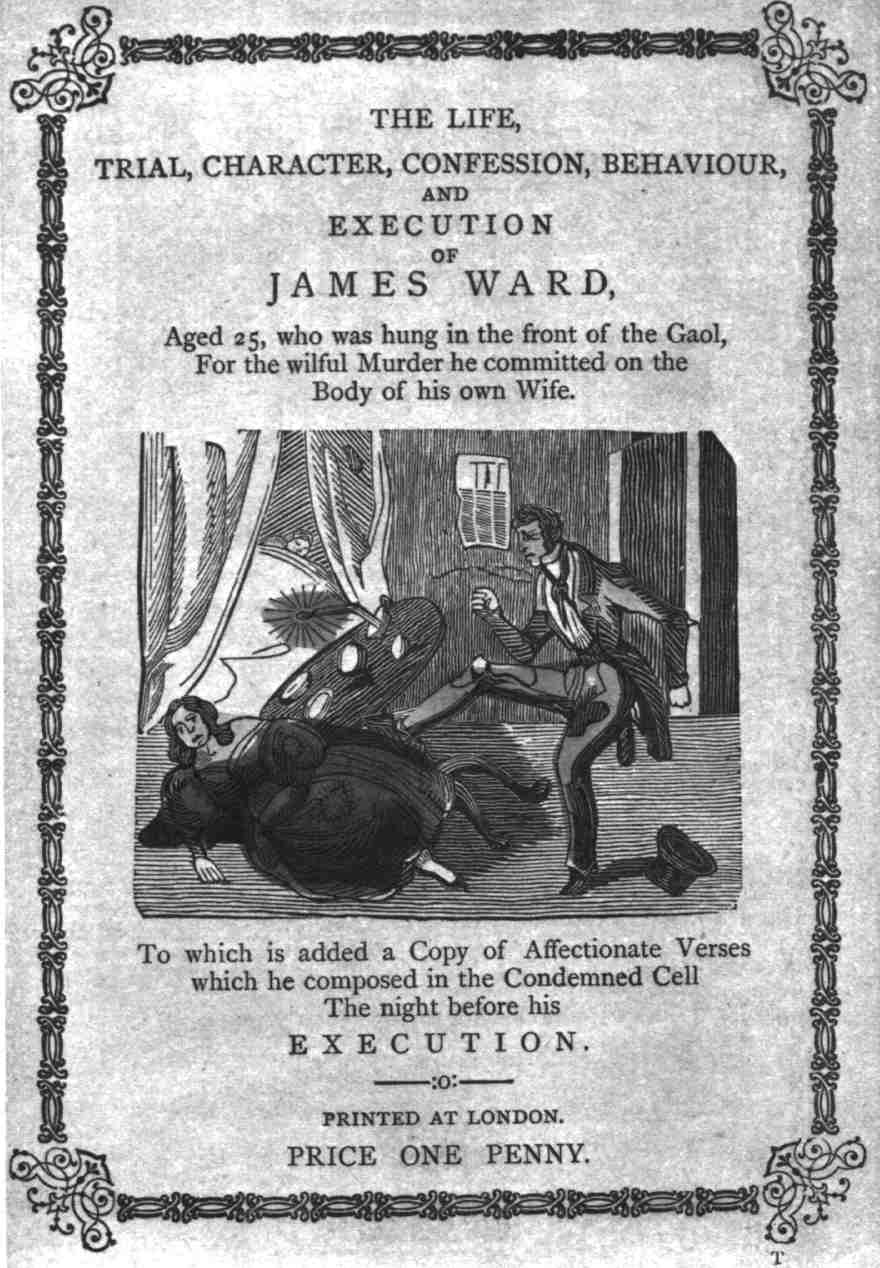

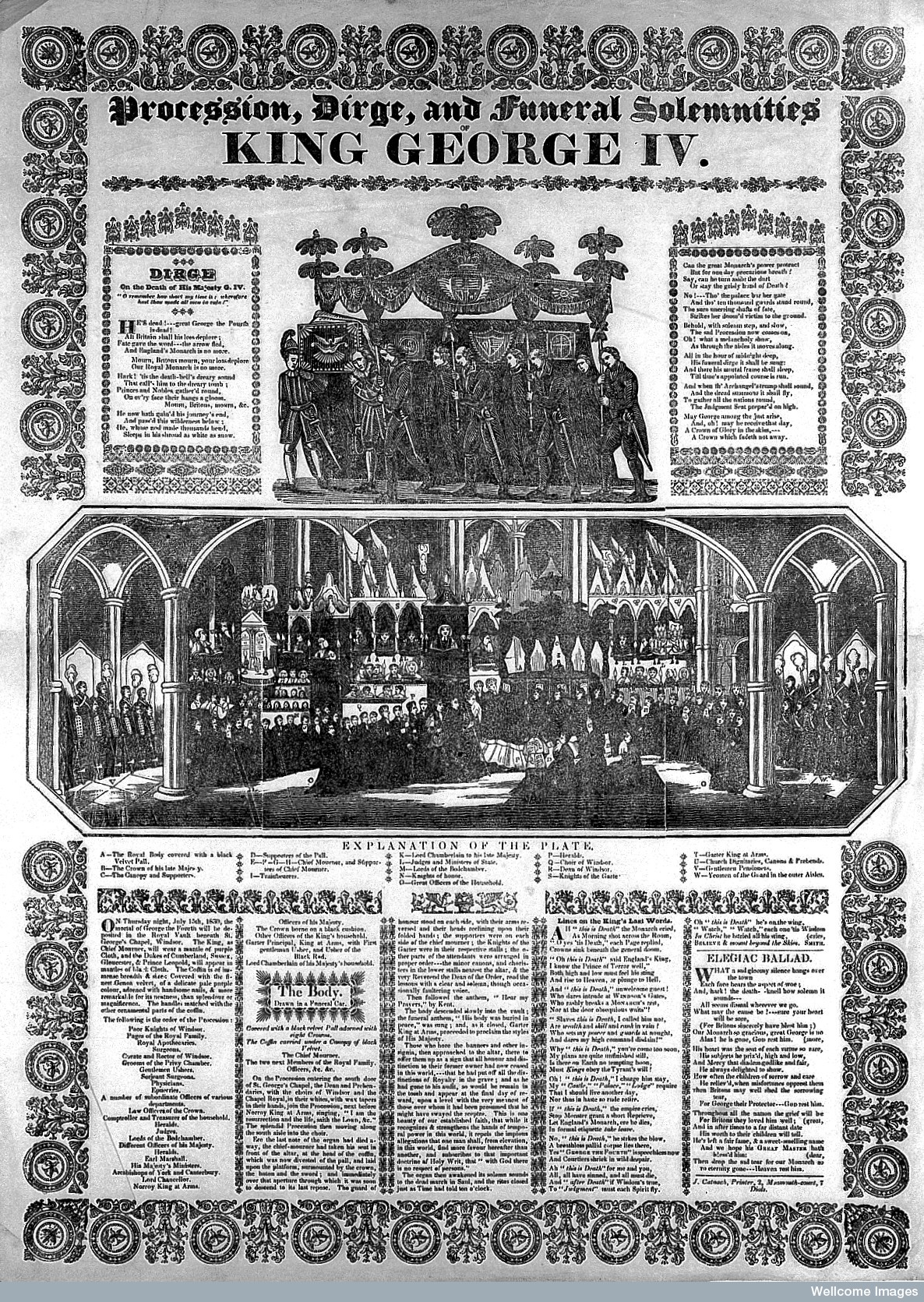

In the 19th century much of the population of Seven Dials comprised immigrants, chiefly Irish and Jewish, many of whom lived and worked in the cellars. The area was particularly favoured by printers of ballads, political tracts and pamphlets who occupied buildings in and around Monmouth Street. Indeed broadsheet printing was pioneered by Jemmy Catnach (1792-1841) who started in Monmouth Street in 1813. His many rivals and followers spread up to Denmark Street and this is almost certainly the reason for sheet music printing originating in ‘Tin Pan Alley’.

A combined work of traffic improvement and slum clearance cut Shaftesbury Avenue through the northwest side of Seven Dials and the St Giles Rookery in 1889. The Woodyard Brewery closed in 1905 when the business moved to Mortlake. Its old premises were converted into box, fruit and vegetable warehouses serving Covent Garden Market. The Seven Dials warehouse became Lepard and Smith paper merchants. The area was densely populated with vibrant markets on each street off The Dials and a great mix of uses.

The rare hand-coloured lantern slide shows The Dials around 1896. The photograph of Earlham Street market is from the same year. Both illustrate the intensive use of the streets in Seven Dials.

Over the years the street names and numbering of Seven Dials were altered several times.The area survived WW2 with relatively little damage. The major upheaval came with the move of Covent Garden Market in 1974 which led to many changes of ownership and use. Both the London County Council and then the Greater London Council had proposed plans which would have seen the demolition of much of the area. These plans were defeated by a community-led campaign by residents and long-standing local businesses.

Seven Dials was deemed to be a conservation area of “outstanding” character and appearance by the Historic Buildings Council in 1974, and one of only 32 conservation areas to receive government funding on this basis. At the time there were around 6,000 Conservation Areas in England. It was also declared a Housing Action Area (HAA) 1977-1984.

From the mid-1970s much restoration was carried out within the parameters of the former GLC Covent Garden Action Area Plan, which aimed to safeguard and improve the existing physical character and fabric of the area and increase the residential population. Within Seven Dials, 90% of the housing stock had lain empty for 40+ years in the expectation of wholesale demolition. The HAA brought it all back into use as well as encouraging new public and private housing. For more information about the journey from demolition to conservation, visit the Trust’s company website.

A particular triumph has been the reconstruction of the sundial column in the middle of Seven Dials, largely funded by private subscription. The original Roman Doric column designed by Edward Pierce was taken down by the Pavement Commissioners in 1773 (and later partially re-erected at Weybridge as a monument to the Duchess of York). The Seven Dials Trust (then known as the Seven Dials Monument Committee) raised the funds and commissioned an exact replica from A.D. Mason of Whitfield Partners Architects. This was based on Pierce’s original measured drawing in the British Museum and the Weybridge remains. The unusual foundations, twice as deep as the Sundial Pillar’s height, were designed by Roger Howard, Hockley and Dawson structural engineers. The bulk of the masonry was executed by youth trainees from Vauxhall College and Ashby & Horner. The column was erected in 1989 as a dramatic symbol of the regeneration of the area. This was the first project of its kind in London since Nelson’s Column in the 1840s.