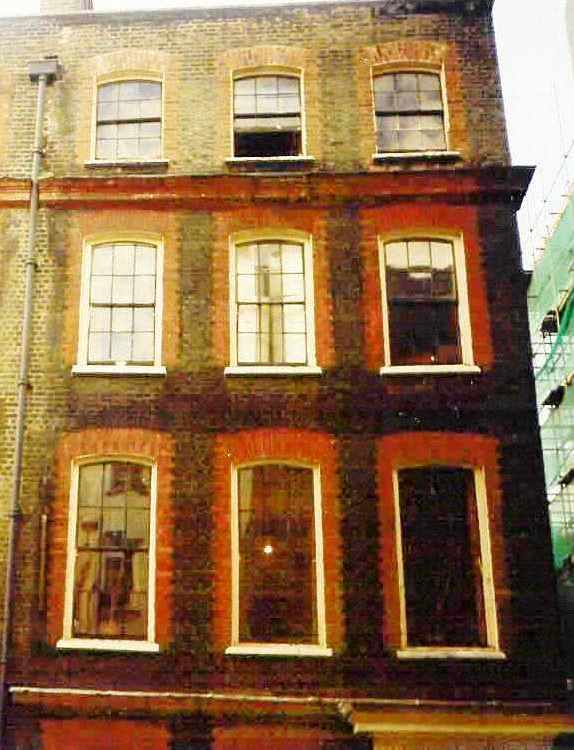

There are many fine brick frontages in the Study Area and it is important they be properly maintained and, where possible, enhanced.

On the Seven Dials Conservation Area side, the two predominant forms of brickwork are Georgian stock brickwork, much of it dating from the re-facing of the original houses in the early 1800s, and late Victorian or Edwardian red brickwork, associated with the redevelopment of Shaftesbury Avenue in the 1880s.

On the Covent Garden Conservation Area side, the massive ex-brewery are mainly of London Stock, sometimes with decorative black engineering bricks.

Cleaning

The cleaning of brickwork should only be entrusted to a specialist contractor and never undertaken by an amateur or general contractor.

Old London stock brickwork is normally a dark yellow-brown colour. If it is over cleaned it becomes a harsh, bright yellow which is not how it was intended to appear. Indeed, such brickwork was often artificially darkened by soot-washing in the late 18th and 19th centuries. It is best to leave stock brickwork in this condition, and not to clean it but to tone it down as necessary with soot and water or a modern substitute (such as a mix of black paint and water to a 1:16 consistency). Soot-washing has a practical basis, as it helps to disguise the damage and patching caused by periodic repairs and repainting.

The treatment of the listed buildings on the Comyn Ching site facing Monmouth Street is a good example of the sensitive treatment of old London stock brickwork which should act as a model for the treatment of old brickwork elsewhere.

In the case of Victorian and Edwardian brickwork, the elevation was usually meant to be bright. Often the red brick was combined with terracotta or stone ornament to create a cheerful multi-coloured effect. It is therefore generally appropriate to clean Victorian brickwork, but great care should be taken not to damage the surface or texture. Simple washing with water, either by hand or with sprays, is usually adequate, or steam cleaning.

Sandblasting (abrasive) cleaning should not be attempted. Acceptable methods of dry cleaning are now being achieved. Microparticle cleaning systems have had particularly impressive results, as demonstrated at the Natural History Museum, Buckingham Palace, the Ritz Hotel and Apsley House. It is a good idea to experiment with a sample section before attacking a whole facade with irreversible results. It should be remembered that the façade materials are historic and may not clean up to look as new.

Diluted hydro-fluoric acid may be used to clean very dirty brickwork which should be followed by a systematic neutralisation process and rinsing. Alkaline and other chemical cleaners are not recommended since they generally contain soluble salts which tend to corrode the bricks. Health and safety of workers and pedestrians must be considered with all applications, particularly chemical. Modern paint can be removed with hot air paint strippers, although great care is needed to eliminate any fire hazard to adjoining woodwork and hidden areas.

Pointing

It is easy to damage old brickwork by inappropriate pointing. It is important to use both a correct mortar mixture and appropriately prepared joints. Mortar used for repointing historic buildings should be based on lime rather than cement for practical as well as aesthetic reasons. Ready-mixed lime mortar for repointing the brickwork of historic buildings is commercially available. The new mix should be the same as the original. Pointing of old brickwork should have a neat flush joint and never a weather-struck joint proud of the surface.

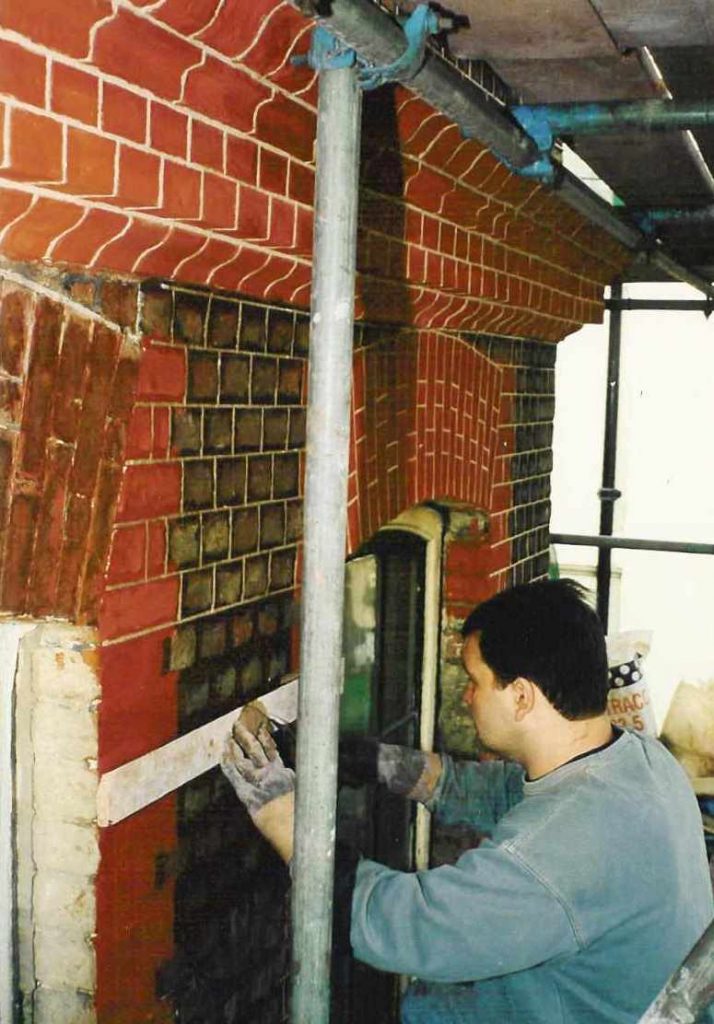

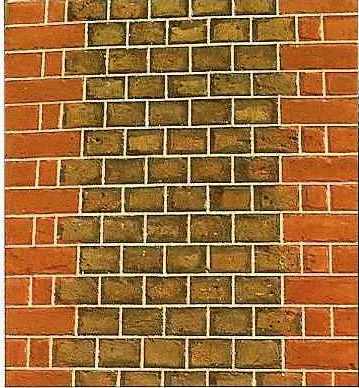

Traditional tuck pointing, which gives the effect of very narrow joints, is a feature of London’s late-Georgian brickwork and several examples survive in Seven Dials. Such tuck pointing should always be preserved and carefully restored as necessary by skilled pointers.

Further information can be found in the Historic England (English Heritage) document, Brickwork Pointing and in their series ‘Practical Building Conservation: Mortars, Renders and Plasters.’

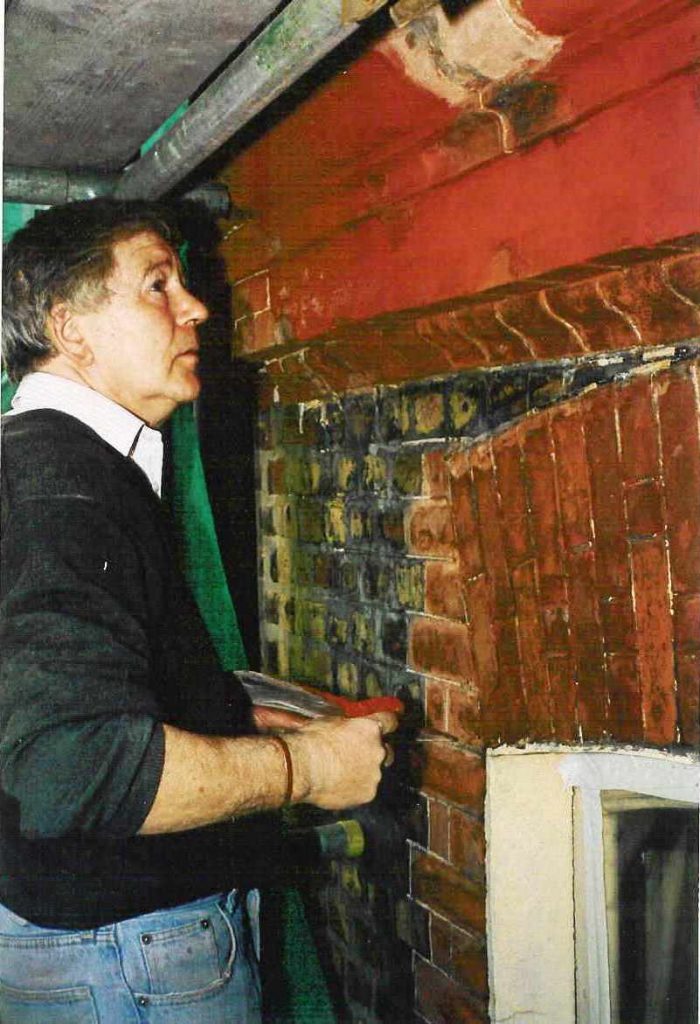

The following sequence of images shows the restoration of tuck pointing on an early 18th century house.